August 23, 2008

We have been anchored off Nebul village in the far north of Ambrym Island, Vanuatu, since Monday, August 18. We have been so busy with the ‘Back to my Roots’ festival we have not had the time to update our blog until now. A lot has happened during these past days and there is much to tell. Our experience is much better conveyed by photos and video but we will be unable to post any of these until we return to Port Vila in 10 – 14 days, depending on weather. The people of north Ambrym have been fantastic and the festival was extraordinary. It ended with the most famous dance of Vanuatu, the Rom dance, that is only performed here.

Passage to Ambrym.

We left Awai Island in the Makelynes on Monday (Aug. 18) with the promise of 15 knot winds from the SSE — good enough for the 36 nautical mile trip to north Ambrym. There is a very strong current in the channel that separates the Maskelyne Islands from Malekula. Fortunately it was a fair current that morning and we made over 8.5 knots through the channel. As we headed almost due north and moved away from the islands the current disappeared and so did the wind and we had to motor until we ‘turned the corner’ past the big bulge in Ambrym Island and altered course to the northeast. The very high twin volcanoes that dominate central Ambrym diverted and accelerated the wind up the western coast and allowed us to finish the passage under sail. The Mt. Benbow and Mt. Marum volcanoes are quite active and their ash plain takes up one-third of the island’s area. The anchorage off Nebul village was filling rapidly and there were at least 8 sailboats within view coming up behind us and half a dozen ahead of us. We monitored the marine radio traffic and learned from ‘Rise and Shine’ that anchoring in close to the shore would be a mistake — their anchor rode was entangled in rocks and coral. Unexpectedly, we got a radio call from ‘Vera’ and learned that they were just 6 miles ahead of us, having spent the previous day at the hot springs area of Ambrym Island. When we arrived they directed us to a place just to their port side. Michael had dived on his anchor and the nearby sea bottom and found only black volcanic sand. We are sitting in nearly 75 feet of water. I would not feel comfortable anchoring in anything deeper. We put out every last foot of chain we have (265 feet). You have to put out lots of anchor chain because strong gusts of wind (williwaws) come thundering down the slope of the volcano, straining anchors and making boats swing and dance. Everyone is aware that a few years ago some boats dragged out to sea (but recovered) and that last year one boat wound up on the reef at nearby Olal. The whole village of Olal came out and pulled the boat off the reef.

By the end of the next day there were 25 boats in the anchorage plus some overflow at the nearby Ranon village anchorage. Two fully crewed sailing superyachts also showed up — Silver Tip and Squall. Luc and Jackie from Sloepmouche once again acted as the liasons between the ‘fleet’ and the villages involved in the festival. Every evening they would make annoucements on the marine VHF radio with information on times, places, and events. There is no hotel or airport in north Ambrym, no roads or electricity, and only a single pickup truck, so it is very hard to attend the festival if you do not have a boat. Nonetheless, there were eight tourists who took the cargo steamer from Port Vila and stayed either at the mission house or on the floor of the rural cooperative bank. A four-man French film crew was also in attendance, having received permission to make a movie of the event. The film crew was not friendly and took it as their right to jump in front of us with their camera and sound boom, occasionally blocking the view at key moments. Back to my Roots Festival.

We dinghied to shore at 8:30 am on Wednesday for the first day of the festival. We were greeted by Zebulon Taleha, a barefoot and handsome 20 year old of Rantvetgere village. His job was to guide a group of us to the ritual dancing grounds every day. I am not sure why, but Zebulon took a particular liking to me. He treated me as if I was the ‘chief’ of our small group of yachties. He walked along side of me answering questions and offering explanations. Our group would not come or go until Zebulon asked for my assent. My connection with Zebulon added importantly to our experience as described below.

The ritual grounds are near the Kastom (traditional life) village of Halhal. To get to Halhal we walked thirty minutes along a beautiful coastal path that is intensely lush and green. Just before the northern-most village of Olal, we took a simple foot path into the interior. For another 15 minutes we walked through groves of coconut palms and forest until we reached the ritual grounds. It is a small area of grass with large tamtams –, logs with intricate faces carved on them and then hollowed out for drumming. The tamtams on north Ambrym, as well as wood carving more generally, are considered the finest in Vanuatu. They take hundreds of hours to produce. Traditionally, those making illicit copies of tamtams were executed. The largest tamtam at the ritual ground is 15 to 20 feet tall. There is also carved stone sculpture. In the forest just 50 meters away is a grass hut (nakamal or mens clubhouse) and surrounding area that is reserved for men. Here men dress (or undress) themselves for rituals, drink kava, and store ritual items such as the distinctive club used to kill pigs, a key element in north Ambrym rituals now that ritually killing humans is tabu. Interestingly, the men that were to be ritually killed and eaten were called ‘long pigs,’

Once men reach maturity, they begin the quest to reach higher levels (grades) in society in order to earn respect for themselves and their spirits when they die. To do this they must own many pigs and use pigs as currency to advance in grade. In north Ambrym there are 14 grades although no man currently alive is higher than grade 11. Men must also pay with pigs to acquire a bride. Zebulon is a grade 1 and is unmarried as he has not acquired the pigs necessary to advance in grade much less marry. In order to take part in the ritual events we were to witness, a man must have a sufficiently high grade and/or pay a price in pigs for the honor. It is a great honor to be a costumed dancer in the Rom dance and men must pay their chief in pigs for that honor.

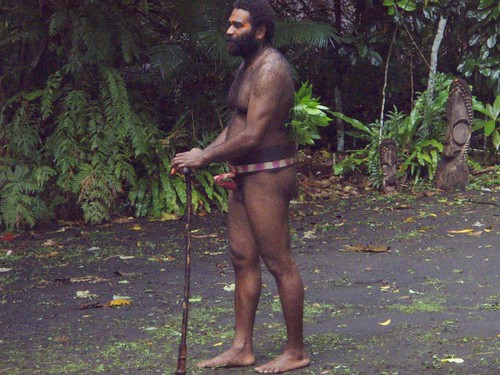

On the way to the ritual grounds we stopped at Zebulon’s house and he gathered up a load of carved bamboo flutes that his father had made. They are beautiful and inexpensive so we bought enough to outfit a small orchestra. About 200 meters from the ritual ground, there were young men in the path collecting the admission fee of 7000 vatu per person for the three days (about $80 per person). As a trade good, we brought along a brand new Camelpak backpack, the kind with a water bladder and drinking tube plus plenty of zippered pouches for storage. We thought this backpack would be perfect for someone trekking up and down the volcano. We asked if we might trade this backpack for admission for the both of us. The young men taking the admission fee could not make this decision themselves, they had to ask the chief. Two minutes later a burly bearded man wearing only a namba (penis wrapper) walked up to me and, in accented English, asked to see the backpack. We bargained for a minute and a deal was struck — the backpack plus 2000 vatu ($21) would get Laura and I in for all three days. One of the young ‘ticket takers’ was delighted. He is the son of the chief and he put on the backpack and wore it for the rest of the day. We saved nearly $140 and made someone very happy.

Speaking of nambas, on the walk to the ritual grounds, Zebulon quietly sang. At one point he sang “Oh when the saints go marching in; Oh when the saints go marching in; I want to be in that namba; When the saints go marching in.” I am not sure whether he knew the word as “number” or “namba”. The latter would seem a more likely phrasing to him.

The seating for us yachties consisted of two bamboo poles set on trees branches. Laura and I brought small cushions. Some yachties had small folding chairs which were much more comfortable. Part of this bamboo seating area was covered by thatch augmented by a plastic sheet. The covering is important since it has rained about 20 times a day since we arrived — and this is the dry season. The tall volcanoes that produce the williwaw gusts also cause it to rain incessantly over north Ambrym. Drying laundry is pretty much impossible. But this weather is good for growing yams and taro in the rich volcanic soil.

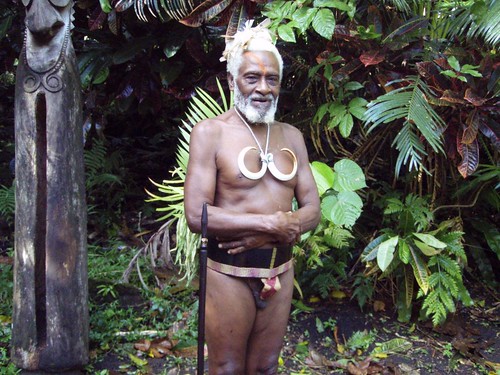

The chief who traded the backpack from me was the master of ceremony for this event. His name is Napong Norbert and he is a very charismatic individual. He described and interpreted every dance and ritual act in both pretty good English and very good French. It is likely that he used French for the benefit of the French film crew as there were no other Frenchmen in attendance (but there were three Belgians). During the colonial period, Vanuatu, then known as the New Hebrides, was jointly administered by England and France. There are French speaking (and nominally Catholic) villages next to English speaking (and nominally Presbyterian) villages. Kastom villages tend to be in the interior of islands.

All the foreign guests were asked to leave the ritual grounds so that we could be led in by the chief and other high grade men dancing the welcoming dance. Most of these men were between 40 and 80 years old as it takes many years to achieve a high enough grade. (Young men danced in most of the other dances.) The male dancers were followed in my dancing barebreasted women in grass skirts who likely are their wives. Then the foreign guests walked behind until we were in the ritual grounds. There were also many ni-Vanuatu (local Vanuatans) were stood in the background to watch, particularly on day three when the Rom dance was performed. This festival was organized by a number of different villages so there were a number of chiefs present. Chiefs carry carved wooden walking sticks as badges of office.

- Rom dance

The dances that were performed during the first two days of the festival did not involve intricate steps. The men typically were in a tight circle with their bare butts facing us, and they stomped to the beat of the tamtams while singing or chanting in their local language. All the men wore a leaf namba that attached their penis to a bark belt. Various kinds of leaf foliage stuck into this belt covered the small of their backs. The dancing was very energetic and the songs and melodies were mesmerizing. I will leave it for the video to describe the action. On both the first and third days of the festival, a pig was ritually killed. On the first day it was a smallish pig that squealed mightily. We did not know what was about to happen but had some inkling that the pig might meet with violence. Chief Napong Norbert spoke in the local language and then took a club to the pig. It was a bit of a shock to us. That pig was served for lunch two days later.

There were food stalls at one end of the ritual grounds. Women sold laplap, bananas, coconuts, boiled eggs, fried dough, bread rolls with meat inside, and nangae, on oval, nut-containing fruit that tastes like an almond. A dozen nangae are sold skewered on a thin bamboo reed, and are quite delicious. Laplap is a pasty mixture of taro root and yam covered in coconut cream and served on a banana leaf. The food was very tasty and inexpensive. I also indulged my recent fondness for kava with help from Zebulon. At the end of the second day we went to the nakamal of one of the chiefs, and he served me and the Veras some potent fresh kava. We also had some kava on the third day in Olal village.

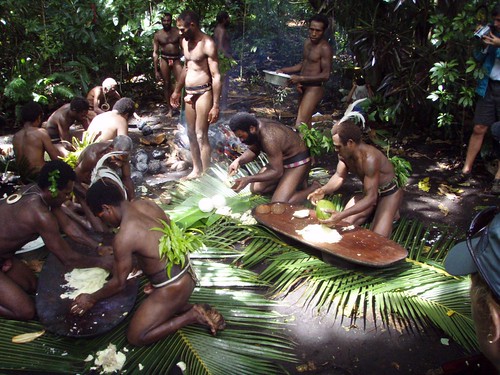

Part of the activities on the second day was a communal lunch. The buff young men of low grade prepared most of the food. It seems that low grade men must prepare their own food and only higher grade men have it prepared by women. The food preparation was in the men’s only area next to the nakamal — a woman could be killed for entering this tabu area. I went there to take photos and some of the women cruisers then gingerly entered as well. One of the chiefs told the women yachties to leave but then the highest chief (by grade), Napong Norbert, over-ruled that chief and said that foreign women could enter. The food preparation was as energy-intensive an activity as the dancing. Wearing only their nambas, the young men scraped coconut meat and squeezed it into coconut cream, and collected firewood and roasted breadfruits. They pounded the cooked breadfuits into paste and laid the paste onto large banana leaves. Hot stones were extracted from the fire and put into open coconuts in order to heat the coconut water which was then worked into the paste. The large sheets of paste where covered with coconut cream and then cut into pieces. The work was so grueling that men would rotate into and out of tasks to give each other a breather. While this was going on, the wives of the high grade men sat some distance away and roasted yams on an open fire. They would reach into the fire to snatch out a yam and proceed to scrape its exterior with the edge of a tin can top. They did this repeatedly, scorching a yam, scraping it, and then repeating the sequence. Laura and I found the food a bit on the starching side and prefered the bread products at the food stalls, but the preparation was really a very interesting sight.

The famous Rom dance was performed on the third and last day (yesterday). The Rom dance is connected to a secret and sacred society of men that remains a mystery to outsiders. I asked Zebulon about it and he provided only ambiguous responses. Fantastic and fearsome masks and full body costumes of banana leaves are one distinguishing features of the Rom dance. These costumes are worn by those being initiated into the secret society and they must make their own masks in secret and according to secret rules. Any outsider who witnesses a mask being made is to be whipped with nettles, or pay a fine (a recent and welcome amendment to the rules). Members of this secret society are keepers of the powerful ‘black magic’, a set of magic skills that can kill men or make the yams grow. Zebulon is hoping to be an initiate of the Rom secret society next year and dance in full costume. We hope to be there. Those who were initiated into the secret society in the past, including all of the chiefs, also danced in the Rom dance but wear only nambas. The Rom dance has a whole different look and feel to it than the dances of the previous days. The men stomped and sang more intensely and seemed in a trance-like frenzy. Sweat poured from bodies. I can only imagine how steamy it must have been for the young men who were completely covered in banana leaf costumes with large, heavy masks on their shoulders and covering their head. Toward the end of the dance, a very large pig was brought out and ritually killed and then left to the side as the rituals continued. The ritual grounds were crowded with ni-Vanuatu who came to see their chiefs and their sons dance. It is said that the yam harvest depends on it. The final dance is a farewell dance that is also a bit of a frenzy. Inside there was a tight circle of singing and dancing men. Outside of that circle women in grass skirts were pulsing slowly to the beat. The foreign guests were invited to join. A gentle rain fell even though it was sunny — and the dancers bodies were glistening. I danced with the men while blindly shooting digital still pictures at very close range while Laura danced with the women and took video.

After the festival was over, there was a banquet in Olal village for the yachties. Some chiefs and those who organized the festival also attended. There was a formidable spread of local foods including the ritually killed pig from the first day of the festival. While waiting for the banquet to begin, Zebulon approached me and said that one of the chiefs wanted to give me his chiefs walking stick. He brought over Chief Massing, who seems to be about 80 years old. We had met Chief Massing, who has some close connection to Zebulon, on the first day of the festival and took a great photo of him. We printed that photo on glossy photographic paper on the boat and gave it to Zebulon to give to the chief on the second day. The chiefs walking stick he gave me had been used by his father, Chief Naroum Naim, and so was quite old. I was quite taken aback by the honor accorded me. Perhaps Chief Massing was grateful for that photo, or perhaps Zebulon persuaded him that I was a chief lacking a walking stick. The people of north Ambrym were uniformly generous and so this act of kindness may not be as unusual as it seems. Zebulon told me afterwards that a man of my age and status must have a chiefs walking stick, and now I do.

M.

[flickrvideo width=”640″ height=”480″]http://flickr.com/photos/sabbatical3/3229479243/[/flickrvideo]

Men Cooking Video